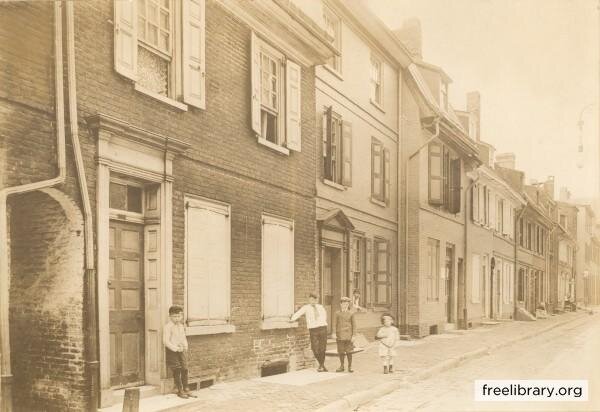

Elfreth’s Alley (then called Cherry Street) as it looked in 1910. #114 Elfreth’s Alley is in the foreground, and #124 and #126, the museum houses can be seen to the right, missing their pent eaves. Image from the Free Library of Philadelphia’s "Historical Images of Philadelphia” collection, accessed via PhillyHistory.org.

In Episode 6 of The Alley Cast, we discuss housing in Philadelphia--how it changed in around the turn of the 20th century and how some parts of the city were neglected into such disrepair that a multitude of organizations were created to try to fix them. But we will also be exploring an idea that we touched on a little in episode 5 and which we will continue to engage with through the end of this season. That the ways in which city neighborhoods are labeled--as factory districts, or quote unquote “slums,” or even historic--are tied up in the priorities of those with power, privilege, and speculative financial investment in those neighborhoods. These labels often determine the options available to those without power and without privilege who live and work in these spaces. And sometimes the labels applied by city planners, reformers, investors, and preservationists can determine the future of a neighborhood--for good or bad, or simply for different--despite the wishes and actions of the people who live and work there.

J. M. Brewer’s 1934 map of Philadelphia is an example of the kinds of neighborhood rating maps that we now collectively refer to as “redlining” maps. Here, Brewer uses a pink color to indicate majority-Black neighborhoods. Green and Blue refer to Italian and Jewish immigrants respectively.

FULL TRANSCRIPT FOLLOWS LIST OF SOURCES

List of Sources

“Annual Report, 1918-1918,” Civic Club of Philadelphia.

Arnold, Stanley Keith. Building the Beloved Community: Philadelphia's Interracial Civil Rights Organizations and Race Relations, 1930-1970. 2014. 69.

Blakney, Sharece, “Armstrong Association of Philadelphia,” Encyclopedia of Philadelphia.

Brewer, J. M.," “J. M. Brewer's Map of Philadelphia” (1934) via PhilaGeoHistory.org.

Cooper, Brittney C., Beyond Respectability: The Intellectual Thought of Race Women Urbana; Chicago; Springfield: University of Illinois Press, 2017.

Delp, Bob, “Frances Anne Wister (1874-1956)” La Salle University Digital Commons.

DuBois, W. E. B., The Philadelphia Negro: A Social Study, 1896.

“Elfreth’s Alley Committee Report, 30 November, 1940,” Philadelphia Society for the Preservation of Landmarks.

Finkel, Ken, “The Quintessential Object of Industrial Philadelphia” PhillyHistory.org. October 25, 2012.

Hunter, Marcus Anthony, “Black Philly After The Philadelphia Negro,” Contexts, The American Sociological Association, Volume: 13 issue: 1, February 1, 2014: page(s): 26-31.

James, Milton M. "The Institute for Colored Youth." Negro History Bulletin 21, no. 4 (1958): 83-85. Accessed July 31, 2020. www.jstor.org/stable/44213172.

Jones, Beverly W. "Mary Church Terrell and the National Association of Colored Women, 1896 to 1901." The Journal of Negro History 67, no. 1 (1982): 20-33.

Muhammad, Khalil Gibran, The Condemnation of Blackness : Race, Crime, and the Making of Modern Urban America, Harvard University Press, 2010.

Newman, Bernard, “Housing in Philadelphia,” Philadelphia Housing Association/Commission, 1921.

“Organized in 1894 by prominent Philadelphia women…,” Historical Society of Pennsylvania.

Roney, Jessica Chopin, Governed By a Spirit of Opposition: The Origins of American Political Practice in Colonial Philadelphia.

Stevenson, Sarah Yorke, “Annual Address by the President of the Civic Club, 1894”

Waldo, Fullerton Leonard, Good Housing that Pays: A Study of the Aims and Accomplishment of the Octavia Hill Association, 1896-1917. Philadelphia: The Harper Press, 1917.

Wright, Richard R. “The Negro in Pennsylvania: A Study in Economic History.”

Full Transcript

Isabel Steven:

Imagine the flight of a bird in the year 1926. This bird takes to the sky from the eastern bank of the Delaware River and rises up above Camden, New Jersey. Following an air current, it heads West across the river. Below, a ferry makes its way slowly across the water, and above is the elegant Delaware River Bridge -- now the Benjamin Franklin Bridge. The bridge has just been dedicated during the celebration of the American Sesquicentennial anniversary, and for the next three years, it will be the longest suspension bridge in the world. The bird soars in the shadow of the bridge, and then sweeps along the piers of the Philadelphia waterfront where raw materials enter this city and finished products leave. Up above the piers is a narrow row of warehouses and beyond them, a train trundles past, raised above the street, and gleaming in the sun. The Frankford Elevated is just a few years old, connecting Philadelphia’s Northeast with its downtown. The bird drifts down past the El and alights on a peaked dormer. Though the sun still shines brightly, the houses along this short block of homes look drab and sooty. Wooden window frames have sagged and warped. This is Cherry Street, formerly known as Elfreth’s Alley.

Ted Maust:

Welcome to the Alley Cast, a podcast from the Elfreth’s Alley Museum in Philadelphia. We tell the stories of people who lived and/or worked on this street, which has been home to everyday Philadelphians for three centuries. While we start in this neighborhood, we will explore connections that take us across the city and around the globe.

Today we will be discussing housing in Philadelphia--how it changed in around the turn of the 20th century and how some parts of the city were neglected into such disrepair that a multitude of organizations were created to try to fix them. But we will also be exploring an idea that we touched on a little in episode 5 and which we will continue to engage with through the end of this season. That the ways in which city neighborhoods are labeled--as factory districts, or quote unquote “slums,” or even historic--are tied up in the priorities of those with power, privilege, and speculative financial investment in those neighborhoods. These labels often determine the options available to those without power and without privilege who live and work in these spaces. And sometimes the labels applied by city planners, reformers, investors, and preservationists can determine the future of a neighborhood--for good or bad, or simply for different--despite the wishes and actions of the people who live and work there.

Episode 6: Housing, Urban “Decay,” and the City of Homes

City of Homes

Isabel Steven:

Let’s rewind a little. We’re going to be talking about homes, neighborhoods, and the city and how those various pieces and scales related and I think it is helpful to start at the beginning of Philadelphia.

Before there was a city, of course, the Lenni-Lenape Indians had lived on this land for thousands of years. When William Penn was granted the charter to create a colony here, it continued a process of genocide and forced removal that would leave the Lenni-Lenape people decimated and scattered. While many Lenape were forced west to Oklahoma, descendants of the Lenape remain in this area and several groups have achieved state recognition in New Jersey and Delaware. The Lenape Nation of Pennsylvania is headquartered in Easton, PA, though the state of Pennsylvania recognizes no American Indian nations.

Even before the Lenape ceded land to William Penn--or are purported to have done so at the Treaty of Shackamaxon, though no record of the treaty’s terms remains--Penn’s surveyors found a site suitable for a city, and Penn had a plan of a new city drawn up. The colony of Pennsylvania was to be Penn’s quote “holy experiment” and this new city of Philadelphia was to be a quote:

“green country town which will never be burnt and always be wholesome” endquote.

Penn had seen what the Great Fire of 1666 had done to London, and he decided to build a fireproof city. To achieve this, he instructed his settlers to build houses in the center of lots, with open spaces all around. Streets in this new city were to be broad and act as fire gaps.

Penn’s plan was predicated on Philadelphia’s new residents spreading themselves evenly across the plan for the city he had drawn up. Instead, they congregated tightly against the Delaware River and spread just a handful of blocks North or South of High St--now Market Street. Instead of building houses on large lots, far apart, lot owners sliced their lots up to fit more people in. Elfreth’s Alley itself was a creation of this pattern of development.

While a few tall tenement-style apartment buildings were erected in the city, legislation in 1895 essentially made them unprofitable. So the row home, early versions of which can be found in Elfreth’s Alley and throughout the old core of the city, became the city’s main mode of development. Between 1870 and 1920, Philadelphia’s population doubled, and simple row homes, known as workingman’s homes, spread out from the city’s core following the new streetcar routes, which in turn spread further to reach these new homes in West Philadelphia, North Philadelphia, and the Northeast.

While these new workingman’s homes were theoretically priced to be attainable for all employed people, in the early 20th century, banks and real estate companies began to “protect” their investments by ruling out certain neighborhoods. The maps that these gatekeepers created of the city often featured red areas where racial minorities, especially Black people, lived. These maps led to the term “redlining,” a practice which systematically limited home-ownership and wealth accumulation in Black neighborhoods across the nation for much of the 20th century. Philadelphia is still one of the most racially-segregated cities in America, in large part because of these discriminatory practices.

The expansion of the city in these shiny new homes and the opportunity it offered left many non-white Philadelphians behind. It also left behind the older neighborhoods, places such as Elfreth’s Alley, now directly in the shadows of factories, slowly falling into disrepair.

The Problem

The infrastructure that connected the city to its suburbs and crossed the Delaware and Schuylkill rivers may have been gleaming and new, but whole neighborhoods in the heart of Philadelphia were struggling with poverty, negligent landlords, and unsanitary living conditions.

It is hard to say what the insides of the houses of Elfreth’s Alley looked like in 1926--we don’t have interior images of the homes. However, various reports on Philadelphia’s housing conditions around the turn of the century give us some idea of how these homes had fared and how the residents in them lived.

In the neighborhoods with the worst housing, a few factors combined to create squalid conditions. For one, much of the most affordable housing was old houses which landlords did not bother to upgrade. These houses, in turn, were often located on old streets with obsolete plumbing which the city did not prioritize. And these houses were squalid. Contemporary accounts describe yards filled with refuse, overflowing privies, and pools of stagnant water. Inside, the many homes were pest-ridden, with threadbare furniture, leaky roofs, and crumbling walls.

Despite the decrepit condition of these houses, they were often overcrowded--such was the demand for housing caused by the influx of migrants and immigrants with meager resources. In some of the most egregious cases, a family would sublet to up to 10 boarders.

For the most part these neighborhoods were located in the 4th, 5th, and 7th wards of the city, where the majority of the population were Black or recent immigrants. In these areas, whole blocks were filled with unsafe housing, but similar conditions existed elsewhere as well. Of special concern were alleyways and courts which were scattered throughout the city. These narrow byways often lacked basic drainage and usually lacked indoor plumbing.

In majority-Black neighborhoods, observers reported a higher number of what were called “furnished room houses,” which offered low-cost rooms for newly-arrived or itinerant residents. These houses were typically in greater disrepair due to the transient nature of residents’ stay, and the financial incentives for operators to both fit more people into the space and pay for only the most urgent of maintenance.

Elfreth’s Alley

Though none of these studies explicitly name Elfreth’s Alley, regular references to alleyways and narrow streets as a city-wide problem suggest that residents of this street may have experienced similar conditions to those described by would-be reformers. Furthermore, certain aspects of these reports match what we do know about conditions on Elfreth’s Alley:

These homes which had been built for single families with space for artisanal production were now primarily sleeping spaces. Houses on the Alley were often shared by multiple households or at least multiple generations. Many of the gardens were built up with rear tenements, accommodating a second household (and sometimes a third) on the lot originally designed for one.

In 1880, for instance, Ellen and William Dannehy, the pearl button makers we met in the last episode, lived in #122 with Ellen’s mother and stepfather, as well as the stepfather’s father and brother. Another couple lived at the same address, possibly in one of these back tenements.

Indoor plumbing came to homes on the Alley relatively late--perhaps as late as the 1930s--and privies (likely shared) were still fixtures of the narrow yards that remained. In 1921 there were as many as 13,000 privy vaults on unsewered streets in the city. Public water for the Alley’s residents was provided by two hydrants, one on Front Street and one on 2nd. Older wells on the street may still have been in use, but would have been prime vectors of disease given the proximity with privies prone to overflow.

The Folks in 135

In 1930, Robert, Gladys, and Goldie Morton, Charles and Elinore Wilson, Nettie McCrae and her infant Robert all lived in house #135.

In Episode 5, we quoted W.E.B. DuBois’ description of the isolation experienced by Black people living outside the 7th ward and got a small sense of the isolation that this household of three Black families probably felt living on Elfreth's Alley, with exclusively white neighbors. DuBois also describes how prejudice from white neighbors and landlords or real estate agents affected housing for Black Philadelphians living in white neighborhoods:

”Here is a people receiving a little lower wages than usual for less desirable work,” DuBois writes, “and compelled, in order to do that work, to live in a little less pleasant quarters than most people, and pay for them somewhat higher rents."

Facing these economic pressures, many Black residents outside of the 7th Ward found substandard housing. DuBois also notes that these pressures drove Black families to crowd into quarters that they were able to find. That the families in #135 in 1930 followed the same housing patterns as DuBois described three decades earlier may seem surprising, but sociologist Marcus Anthony Hunter has shown that many of the conditions DuBois reported continued into the mid-to-late 1930s.

House #135 probably didn’t feel super cramped even with seven of them sharing it; the house enjoys the widest street frontage of any house on Elfreth’s Alley and includes a full three floors in addition to a garret right under the roof. 30 years earlier, the same house had held 11 members of the O’Drain family and two household staff. Yet it was probably not comfortable; If there was indoor plumbing in #135, it was likely rudimentary. It would not be surprising if there was an outhouse behind the house.

The owner of the house, Richard Weiglein, likely neglected the property and in 1932, #135 was seized by the First Mortgage Corporation. By 1941, it was condemned suggesting that it may have been in serious disrepair during the time it was home to the Mortons, Wilsons, and McCraes.

The “Do-Gooders”

The people who lived in the overcrowded old houses, on Elfreth’s Alley and around Philadelphia, didn’t leave many records behind; we know about the poor state of housing because reformers and philanthropists took great pains to document it even as they worked to improve those conditions.

Philadelphia has a long history of charitable organizations, dating from its founding charter in 1682. That founding document made no provision for most public services and voluntary organizations filled in, sometimes imperfectly. The city government grew in the early 19th century, but by the end of the century, the Philadelphia city government was in trouble. Decades of political corruption had weakened the civil infrastructure and siphoned off municipal funds. Financial panics and depressions reduced city revenue from taxes. These financial upheavals and the volatility of the industrial city left thousands of Philadelphians out of work and pushed many more into poverty. The contraction of the city government’s operations worsened the conditions for those living at or below the poverty line.

The combination of this need and the city government’s inability to perform necessary functions brought about another age in which private, voluntary organizations served important functions: providing a variety of services for the public, lobbying the government to advocate for reforms as well as the resumption of basic government functions, and finally contributing financially, through both charity and investment, in the city’s poorest neighborhoods.

Among the many private philanthropic or reform-oriented clubs were the Civic Club, the Octavia Hill Association, and the Philadelphia Housing Commission. These three organizations give us a sense of the larger movement of voluntary organizations.

The Civic Club

At first glance, the Civic Club of Philadelphia looks like any other number of social clubs across American history, offering social interaction and a visiting speaker at each meeting. Yet the Civic Club, founded in 1894, sought to make a real impact in the city of Philadelphia. However, the way they envisioned this impact was steeped in paternalistic rhetoric and discriminatory practices of social control.

The organization’s first president, Sarah Yorke Stevenson described the Civic Club’s aims like this in her 1894 annual address:

“As a body we are pledged to advocate and support any measure the tendency of which is to make Philadelphia morally purer and intellectually broader, that will add to its charitable and educational facilities, and that will make it more important as a civilized center.”

To accomplish this broad goal, the Club initially divided itself into four departments and then evolved into a myriad of committees, tackling everything from public health and child welfare to censorship of motion pictures and Americanization of Immigrants.

By employing phrases such as “morally purer” and making the Americanization of Immigrants an explicit aim of the organization, the Civic Club showed its fundamentally racist and xenophobic worldview in which they sat at the pinnacle of society and sought to bring others into their way of living. This underlying belief drove the organization’s programming, including programs aimed at recent immigrants, especially children, rendering any such programs paternalistic and often racist. The Civic Club was not alone in these foundational beliefs and many other reform and cultural organizations of the era espoused similar aims.

The members of the Civic Club were exclusively women, and many of them were from the old families of Philadelphia, the upper crust of the city socially and economically. Frances Anne Wister, was also a member of the club and would serve as a vice-president from 1907 until her death in 1956 except for a few years in the 1920s. Wister would also serve in leadership positions in a multitude of other clubs and associations, and we will hear more about her in our next episode.

Two other members of the Civic Club were Hannah Fox and Helen Parrish, both from old Quaker families. As early as the 1880s, Fox and Parrish followed the example of a British activist, Octavia Hill, and bought several properties just North of South Street, renovating them and renting them to low-income residents. As Hill had done, Fox and Parrish set rents to return a constant profit of 4-5%. Though this effort had much in common with charitable programs and was an effort to improve the lot of Philadelphians who would otherwise live in substandard housing, it was also fundamentally a capitalist enterprise, promising steady return for investors.

In 1896, Fox met Helen C. Jenks, who became an investor and who encouraged her to expand the modest program. Fox and Jenks took the concept of providing decent, low-income housing, with a return on investment to the Civic Club and members of the Club, including Frances Wister, who started the Octavia Hill Association. The OHA bought up houses on several alleyways throughout the city, refurbished them and rented out. Eventually, the Association created a subsidiary, the Philadelphia Model Homes Company, which built entirely new homes to be rented out to low-income tenants. A key component of the OHA model, drawn from Octavia Hill’s procedures in London, was to deploy volunteer women as “friendly rent collectors.” This was seen as a way to provide a direct line of communication between tenants and the OHA leadership in contrast to the absentee landlords who operated much of the worst housing in Philadelphia.

One important contribution made by the OHA to the city of Philadelphia was a 1904 report that aimed to describe what the organization saw as deplorable housing conditions in the city. This study served as a resource for lobbying the city government to take action. In 1909, the Philadelphia Housing Commission, a coalition of dozens of reform and philanthropic organizations, including the OHA, was formed at least partly in concert with Dr. Richard Neff, Philadelphia’s Public Health Director. In 1913, the PHC gathered a crew of volunteers who moved throughout the city’s narrowest streets and forgotten neighborhoods, documenting the conditions in photographs and filing complaints with the city. The next year, they rented a store-front window and filled it with information and photos about the housing crisis. Yet these tactics had relatively little effect on a city government still mired in corruption.

Around that time, the PHC hired Bernard Newman, a Unitarian Minister. In 1921, Newman and the PHC released a housing report of their own, which again depicted heinous conditions, though it drew greater attention to the role of industrial infrastructure, particularly slaughterhouses, in making neighborhoods unsanitary. Again, part of the PHC’s strategy included repeatedly nudging the city government, and the 1921 report listed some 8,000 complaints it had made via official channels, ranging from “unsafe and defective structures” to “filth conditions.”

Criticisms of the PHC (and some other orgs)

The Civic Club, Octavia Hill Association, and Philadelphia Housing Commission all made their impacts on the city of Philadelphia, but they shared some shortcomings, specifically around race. Historian Stanley Keith Arnold has argued, for instance, that though the PHC involved literally dozens of organizations, it made little effort to involve Black community organizations even as it advocated changes in majority-Black neighborhoods.

Scholar Khalil Gibran Muhammad, in his book The Condemnation of Blackness: Race, Crime, and the Making of Modern Urban America argues that the actions of many of the reform organizations of this era played an essential role in creating the idea of Black criminality in America.

The majority-white organizations formed to improve housing conditions tended to believe two essential things: First, that housing conditions--especially for children--were inherently linked to societal ills, usually defined in vague terms, and second, that statistical surveys, recorded through surveillance of poor neighborhoods by activists, were key to understanding the the impact of poor housing and to making arguments about how to change it.

Neither of these beliefs engaged with the effects of systemic racism, which led to racial profiling, policing patterns, and other racist policies that led to higher levels of arrest and incarceration of Black Americans. Instead, subjective observations showing comparable housing conditions between some Black-majority neighborhoods and neighborhoods with high numbers of European immigrants were used to argue that there was no environmental reason for the arrest and incarceration of Black people.

For many of the reformers of this era, one target of reform was the morality of individuals. While this framework led reformers to engage with European immigrants individually, when it came to Black individuals, race often superseded personal behavior. Khalil Gibran Muhammad highlights a passage from a 1916 passage describing the majority-Black neighborhood immediately surrounding the OHA headquarters as quote “dangerous for women to go into, surface drainage of the most flagrant and revolting kind, privy vaults almost universal.” Why, asks Muhammad, was the neighborhood “dangerous for women to go into” if the only other distinguishing features were A) a majority-Black population and B) unsanitary conditions? Descriptions of other neighborhoods with equally heinous sanitation did not include the same safety warning, showing that even many of the would-be reformers were associating Blackness with criminality.

Black-led philanthropy

Of course, the Civic Club, the OHA, the PHC and other majority-white organizations weren’t the only people trying to fill in the gaps left by an ineffective government. Plenty of majority-Black organizations were doing so too, and had been for at least a century.

In DuBois’ study, he lists a multitude of grassroots efforts to build a safety net for Black communities in Philadelphia. By at least the late 18th century there were mutual aid societies, which provided insurance in the case of sickness or death. By the late 19th century, when DuBois was writing, there were Black-led building and loans associations, elder care, at least one homeless shelter, organizations for racial equity, and even secret societies, which served many of the same purposes as mutual aid associations. Many of the efforts sprung up in Black churches, which acted as sites for public meetings, and whose clergy sometimes acted, in DuBois’ words, as “employment agents.”

Across the nation around the turn of the century, Black women took a leading role in theorizing race and working for racial equity. These novelists, journalists, educators and more took public stances, in published works and oratory to claim a place and a voice for Black women in American society.

In the 1890s, many of these women formed clubs, like their white counterparts. Recognizing a national framework would provide support to club members as well as a unified and more prominent platform, several of these organizations merged to become the National Association of Colored Women in 1896. This organization bore striking resemblance to the General Federation of Women’s Clubs, an exclusively white organization--both worked to advocate for women socially and politically and provided social services in the communities in which their chapters were located. Yet Beverly W. Jones has argued that the NACW had to respond to racism, both in the form of vitriol--as when the president of the Missouri Press Association wrote a public letter besmirching the morals of all Black women--as well as systemic racism.

In addition to the local and national organizations founded by Black leaders, there are a few local examples of more racially integrated organizations. Cheyney University was founded as the first Historically Black College and University in 1837 with a bequest from a wealthy Quaker whose family wealth was created by enslaved laborers. Donations from other prominent white Quakers followed, but from at least 1852 onward, the school was led by Black directors.

In 1908, progressive white Quaker John Thompson Emlen collaborated with Richard R. Wright Jr., a Black doctoral student at the University of Pennsylvania to found the Philadelphia branch of the Armstrong Association, a national organization aimed at improving education, housing, and employment for Black Americans. While running on funding from white donors, the board of the Armstrong Association maintained 50% Black members from early in its existence. This Association, like the OHA and PHC, also published studies on Black living conditions and Black entrepreneurship. In the 1950s, the Philadelphia chapter of the Armstrong Association merged with the National Urban League.

Conclusion

From the 1880s through the 1920s, social welfare organizations made sweeping impacts on the city of Philadelphia and the nation as a whole. These associations brought public scrutiny to unsanitary conditions which unfettered industrialization and lax housing codes had created in many American cities, and attempted to provide healthcare and education to migrants and immigrants, who populated these neighborhoods. The women who organized in these causes became more deeply involved on the political stage, though none could vote until 1920 and many Black women had to fight longer for that right.

The majority-white organizations took center stage, monopolizing the conversation and much of the funding, and have since been thoroughly studied by scholars trying to reckon with their legacy. It is a legacy tainted by racism and paternalism, and one which often inadvertently contributed to the idea of inherent Black criminality, which has driven racist policing practices ever since.

Majority-Black organizations sought to fix the same problems, yet they also had to constantly advocate for their own existence in an era that viewed the pseudo-science of racial difference as legitimate.

In the Philadelphia Housing Commission’s 1921 publication, ‘Housing in Philadelphia,” Bernard Newman described the city government’s infrastructure priorities somewhat dramatically:

“The City knows that while costly boulevards and parkways, palatial public buildings and art galleries, palaces of justice and convention halls and other municipal buildings with their costly embellishments may add to the artistic appearance of a metropolitan city still they serve to emphasize more forcibly the flagrant filth and squalor of the neglected slums; they are often the powder and rouge over the dirt-smeared face.”

Passengers on the newly-built elevated rail passing Elfreth’s Alley might have felt the resonance of this image. Here was an old street neglected for decades, with standing water in the street and privies in the yards. In house #135, the McCraes, Mortons, and Wilsons dealt with the realities of life in a neglected building and inadequate plumbing. And when they slept, they dreamed.

Today, the houses on Elfreth’s Alley not only have running water but air conditioning and wifi. The risk of diphtheria is approximately nil, and the residents for the most part enjoy good-paying jobs. Yet house #139 still has a privy in a small patio beside the house, and it has been listed as a kind of bonus feature when the house has been up for sale. The privy is not in use, obviously, but why keep it? The answer is “history.” What was once a mark of neglect during the industrial era is now a charming relic of the “Colonial” era. This transformation happened over a long time and overnight at the same time.

Next week we will trace the Alley’s trajectory from derelict housing to historic landmark.

Ted Maust:

History is a group effort! This episode was researched and written, by Ted Maust and narrated and edited by Isabel Steven, with research and editorial assistance from Joe Makuc. Cynthia Heider served as a subject matter expert and provided a key, nuanced perspective on the people and organizations we discuss in this episode.

In addition to the sources cited by name, this episode drew heavily on the work of Brittney C. Cooper and Ken Finkel. See the episode page at elfrethsalley.org/podcast for a transcript and a complete list of sources.

Our theme music is the song “Open Flames” by Blue Dot Sessions from the album Aeronaut, used under Creative Commons license.

This podcast is recorded on the unceded indigenous territory of the Lenni-Lenape people, who were and continue to be active stewards of the land. We recognize that words are not enough and we aim to actively uphold indigenous visibility and sovereignty for individuals and communities who live here now, and for those who were forcibly removed from their Homelands. By offering this Land Acknowledgment, we affirm Indigenous sovereignty and will work to hold the Elfreth’s Alley Museum accountable to the needs of American Indian and Indigenous peoples.

Thank you for listening! If you enjoyed this episode, please rate and review us on Apple Podcasts! Be sure to join us next week for Episode 7.

Thank you for supporting the Elfreth’s Alley Museum by listening to this podcast! If you are able to make a financial gift, you can do so at elfrethsalley.org/donate

Thank you and take care!