Mary R. “Dollie” Wyle Ottey (right) poses in costume with her “helpers.” Image from the Elfreth’s Alley Association Archives.

The ongoing pandemic has wreaked chaos on the restaurant industry, closing popular spots and leaving huge numbers of restaurant workers out of work. In this episode of The Alley Cast, we explore the long history of the transience of restaurant work in order to try to gain some perspective on the challenges of today.

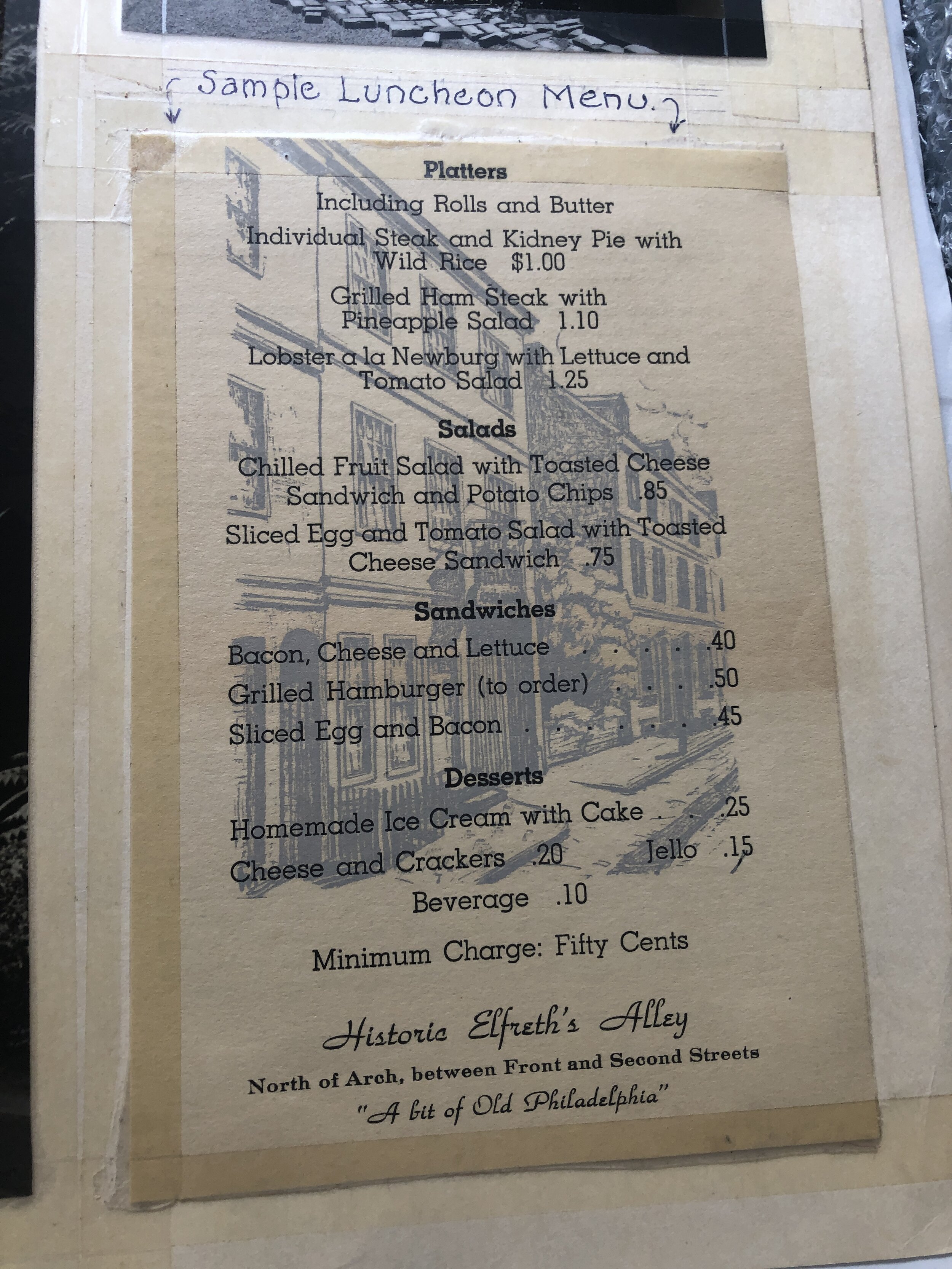

Lunch menu from the Coach House Restaurant in the Elfreth’s Alley Scrapbook.

Special thanks to Paige Bartello and Gwen Franklin, who wrote the first version of this script and did much of the research for this episode.

Learn more about the challenges facing restaurant workers right now: https://www.inquirer.com/news/labor-shortage-pandemic-workers-restaurants-philadelphia-hiring-20210710.html

Contribute to the Restaurant Workers Community Foundation (https://www.restaurantworkerscf.org/) to help workers in need.

Thanks again to our sponsors Linode and the History Department and Center for Public History at Temple University. Support is also provided by the Philadelphia Cultural Fund and the Museum Council of Greater Philadelphia.

SOURCES

Carp, Benjamin. Rebels Rising: Cities and the American Revolution, 173.

City Tavern Timeline,” https://www.citytavern.com/city-tavern-timeline/

“In Memoriam: All the Philly Restaurants That Closed During the Coronavirus Crisis So Far”: https://www.phillymag.com/foobooz/restaurants-closings-coronavirus/

Pilgrim, Danya. “Masters of a Craft: Philadelphia’s Black Public Waiters, 1820 - 50,” The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography 142, 2018.

Thompson, Peter/ Rum Punch and Revolution: Tavern-going and Public Life in Eighteenth-century Philadelphia, (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1999).

Yamin, Rebecca, and R. Scott Stephenson. 2019. Archaeology at the site of the Museum of the American Revolution: a tale of two taverns and the growth of Philadelphia.

TRANSCRIPT

Introduction:

Ask anyone working in the restaurant industry today whether they imagine doing this work for the rest of their lives and you’ll find that the majority will tell you no.

Whether it is a part-time position to pay the bills while in school, or a necessary means to an end before a better opportunity for work arises, restaurant workers are a highly transient group. Turnover rates are high amongst staff, and restaurants themselves open and close in no time at all. The COVID 19 crisis is exacerbating the instability of service industry work. This trend is not exclusive to our present moment however, throughout the history of Philadelphia the food service industry was a volatile realm for restaurant laborers and proprietors. Service industry workers are largely absent from historical records, and those that do appear are difficult to track beyond a single entry. Although the restaurant industry in Philadelphia looks vastly different from its inception in the eighteenth century, we can find threads of continuity between the food industry’s distant past and its current moment. Taverns and restaurants on Elfreth’s Alley likely faced similar challenges and labor turnover rates as the contemporary bars and restaurants that now fill the surrounding neighborhood of Old City. Join us as we explore the transient history of Philadelphia’s culinary labor industry past and present.

Welcome to the Alley Cast, a podcast from the Elfreth’s Alley Museum in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. We trace the stories of people who worked, lived, and encountered this special street for over 300 years. While the stories we tell often center on Elfreth’s Alley and the surrounding Old City neighborhood, we also explore threads which take us across the city and around the globe.

The story we are about to tell you is one of constant change. While working on the initial draft of this episode, the City Tavern in Philadelphia, one of the places we hoped to anchor our story on, permanently closed its doors in response to the Covid-19 pandemic. In a way, this illustrates how the *difficulty* of working and running restaurants in Philadelphia has been one of the few constants in the industry. In this episode we will explore the historic precedents for the dramatic disruptions over the last year The Covid 19 pandemic has impacted our society at every level, especially those who work in food service and the closure of City Tavern hits deeply at our greatest fears and insecurities about the service industry and public history sites more generally.. People who depend on service industry work to live in a city like Philadelphia are experiencing the shortcomings of our economic system to the greatest degree. While this project is about transience, and inevitable change, it is also about crisis.

One of our greatest barriers to making this podcast was the lack of good source material regarding those who worked in Philadelphia’s restaurants surrounding Elfreth’s Alley. While the Alley itself was home to restaurants and food service workers, we simply don’t know much about them. In an effort to make sense of all that we don’t know, we are going to focus on food service industries in the surrounding area before zeroing in on two restaurants which operated on Elfreth’s Alley during the 20th century. We hope to tell the story of food workers on the Alley by illuminating the experience of other restaurants and individuals in the nearby neighborhoods of Old City and Philadelphia writ large. We start this journey during the days of the Revolution, work our way through the emerging Black catering industry of the early 19th century and land squarely on the Alley during the Great Depression through the mid-century period. Get a bite to eat and sit back with us to learn a bit more about Philadelphia’s food service industry.

This is Episode 7: The Servers

Act I:

In Philadelphia’s early days, taverns were humble affairs. While William Penn did not want his new city associated with liquor and vice, he begrudgingly accepted that alcohol would make its way into Philadelphia whether he banned it or not, and granted licenses to sell alcoholic beverages. Tavern operation was seen as one route out of poverty, and many of the city’s poorest residents sold homemade potables out of their houses. Penn stipulated that taverns were to serve quality drink at standard quantities at set prices and decreed that these establishments were not to harbor sedition, gambling or drunkenness. In order to sell alcohol in the new city you would need a license, and to get a license you would need to be an upstanding community member.

Alice Guest was widowed shortly after arriving in Philadelphia in 1683, and left with little but a waterfront cave dwelling like those we discussed earlier in this season. Guest opened a tavern in her cave, and would eventually convert it into a more conventional building, giving it the name of the Crooked Billet. Guest expanded her compound to include warehouses and a separate house, all along a little street called Crooked Billet Alley. She had also managed to acquire another house across Front Street.

Throughout her two-decade career as a tavern operator, Alice Guest crossed every “t” and dotted every “i” of the city’s regulations, but not all tavernkeepers were so conscientious and Philadelphia’s taverns grew their own reputation for public drunkenness. As the city expanded, more taverns were opened, many of them without licenses. The city exploded in size, and as the population increased, so did its taverns, but at a disproportionate rate. In 1693, Philadelphia was home to 2100 people and had 12 taverns. By 1769, less than 100 years afterwards, Philadelphia was home to 28,000 people and had 178 taverns. And by this time, food became a major component of tavern fare--Philadelphia was becoming a city of restaurants.

Just four blocks from Elfreth’s Alley, located at 138 S 2nd Street is the historic City Tavern. In 1772, 53 members of Philadelphia’s elite social class commissioned the construction of a tavern in the heart of Philadelphia. By 1773, City Tavern was open for business. The financial sponsors of City Tavern wanted to build a restaurant that served both alcohol and food to host important men in the nation's biggest city. City Tavern was a big building even in the late 18th century. With five floors and a large porch for outdoor dining, the newly built Tavern was inviting, warm, and bustling. Inside there is a bar room, two tea rooms, three dining rooms and, at the time, the second largest ballroom in America.

There had long been the prevailing notion that taverns exerted influence beyond their doors. By opening City Tavern, Its founders hoped to command the narrative.

City Tavern was a crucial meeting place on the eve of the Revolution. It was frequented by the likes of Thomas Jefferson, Benjamin Franklin and George Washington.

In May 1774, Paul Revere arrived at the Tavern with news of the Parliament's actions in Boston. The following day over two hundred of Philadelphia’s elite met at the Tavern to discuss the decision and to write to Boston officials. The Tavern became for Philadelphia an extension of its political meeting house.

What escapes us as historians is not Philadelphia’s elite and their political expression over drinks, but the political ideas and expressions of those serving drinks. We know so little about those who lived in the servants quarters in the City Tavern. We know next to nothing about those who served George Washington and Benjamin Franklin, and what it must have felt like to be on the margins of their conversation on the eve of the Revolution. What kind of emotions did the impending crisis evoke for those who worked in the service industry?

Act II:

We may not know much about the servants that lived in and worked at the City Tavern, but we can trace the further development of restaurant industry professions through Black caterers in the early nineteenth century. Like the servants of City Tavern before them, Black waiters and cooks existed on the margins of the food service realm and continually had to seek legitimacy as skilled workers.

Dr. Danya Pilgrim, Assistant Professor of History at Temple University, has done significant work on the rise of the Black catering industry in Philadelphia. Here she describes how she conducted her research:

Dr. Danya Pilgrim:

And I was digging through the material. And I found a folder about dinners. I was like, Okay, well, let me just check this out. It wasn't what I went there for. And then I opened it up, and I found 100 years worth of receipts for meals that PSFS had contracted with public waders for and that was really the beginning for me, because then I realized that what I was really going to be able to find was to start with financial records. Right? So psfs, the Mutual Insurance Company. Some of the organizations like the St. Andrew Society of Philadelphia, and look in their financial records, and if they had records for dinners or meals often then there was some other connection in in the archive are in the collection that would lead to what I affectionately call my people in the archival record. So really, I kind of fell down a hole And followed my mind as far as that goes on, and then also to not restrict myself in terms of material. So to not come to the project, thinking, this is the source space that I will use, because I never would have found them in literature. I mean, I found poems, I found books, you know, they're mentioned, my subjects are mentioned in a lot of different places and having to reimagine the archive, right? To think about wills that can tell me about what a home looked like to be able to use insurance surveys, which was also again, right, it was digitized. And that's how I found the first insurance survey. And so those being able to pull all those little scraps of things together, is what enabled me to be able to tell this history.

Early nineteenth century Philadelphia saw an influx of free Blacks in the city. In the 1790s, the Haitian Revolution had driven many French plantation owners to flee to cities including Philadelphia, and they brought the people they had enslaved with them. Under Pennsylvania’s gradual emancipation law, many of those people were freed by law within six months of their arrival. Freedom seekers from the south added to their numbers. By 1820, the city’s free Black population reached 12,000. These newcomers hoped to build lives in Philadelphia, but they encountered discriminatory practices that proved difficult to navigate. Many free Black men found that working as wait staff was one of the few careers open to them as racial barriers hardened in the mid-19th century. In a 1838 census of Black Philadelphia, “waiter” was the second most common profession for men, with 11.5% of surveyed Black men identifying themselves as such. Dr. Pilgrim’s work explores the way both Black men and women participated in the service economy; men primarily served as waiters and women as cooks. They worked in both a public and private capacity, as the city’s elites increasingly held formal private dinners in their homes and hired outside help. These private parties served as measures of elite status for wealthy Philadelphians, and Black caterers were the direct source for lavish dinners. By providing the finest silverware, cuisine, and service, Black caterers established their position as skilled and valuable members of the workforce. Caterers, like event managers today, brought with them a trained staff and were highly sought out by those wanting the best in service at their parties. As they honed their craft Black service industry laborers subverted their marginal position within society and gained prestige within the dining rooms of white elites.

In 1827, Robert Roberts, wrote a manual called THE HOUSE SERVANT'S DIRECTORY, which instructed servants on the art of waiting. Many of his instructions were no doubt useful to public waiters working special events:

Keshler Thibert, reading the words of Robert Roberts: “You must not seem to be in the least confusion, for there is nothing that looks so bad as to see a man in a bustle, or confused state, when he has the management of a party. He should always take hold of his work as if he understood it, and never seem to be agitated in the least.”

“The beauty of a servant is to go quietly about the room when changing plates or dishes ; he never should seem to be in the least hurry or confusion, for this plainly shows that he is deficient of his duty. A man that knows his business well, should take hold of things as a first rate mechanic, and never seem to be agitated in the least. You should always have a quick, but light and smooth step, around the room while waiting; practice will soon bring you to this.”

The craft of Black caterers also extended to performance. Parties in lavishly decorated homes full of paintings and mahogany furnishings were made even more upscale if they were staffed by Black men and women. The ability of the waitstaff to put on a show of elegance was crucial to the level of sophistication attributed to the host’s party. Waiters were also in positions to listen and observe, gaining important insights, such as current trends in menus, decor, and other elements of entertaining, which could be leveraged for future clients.

Some of these men, such as Robert Bogle, Randol Shepherd, and Scipio Sewell built catering empires out of their reputations as waiters, and were considered among the upper-crust of Philadelphia’s Black community, serving in leadership roles in organizations such as the African Episcopal Church of St. Thomas, the Black Freemasons, and the first national convention of free Black Americans, held in 1830. Even as these men built prosperous lives, Philadelphia disenfranchised Black men in 1837, and racist rhetoric and violence in Philadelphia built in the middle of the century. Yet working within the catering field would continue to be a viable career for Black men in Philadelphia at least up through the Civil War.

When we come back, we’ll jump ahead again to the early 20th century, and discuss a sandwich shop on Elfreth’s Alley.

Sponsor Break

Our lead sponsor is Linode. Linode is the largest independent open cloud provider in the world, and its Headquarters is located just around the corner from Elfreth’s Alley on the Northeast corner of 3rd and Arch Streets, right next to the Betsy Ross House Museum. The tech company moved into the former Corn Exchange Building in 2018 and employees have relished the juxtaposition of old and new: Outside, concealed LEDs light up the historic facade, inside are flexible server rooms but also a library with a sliding ladder, and a former bank vault is now a conference room. Linode is committed to a culture that creates a sense of inclusion and belonging and is always looking for new team members. Learn more about job opportunities at linode.com/careers.

This season is also sponsored by the History Department and the Center for Public History at Temple University. Many of the people who have worked on this podcast over the past two years have been alumni or graduate students at Temple University. A special thanks to Dr. Hilary Iris Lowe and the students in her “Managing History” course during the Fall of 2020 who did preliminary research and scriptwork for several episodes this season. Learn more about the department at www.cla.temple.edu/history/ and the Center at sites.temple.edu/centerforpublichistory/

Act III:

In the mid 20th century the restaurant industry had changed only a little from the centuries before. Philadelphia’s food service still depended on the labor of marginalized Americans, still served similar food, and often catered to the elites. Dollie Ottey, the owner of the Hearthstone, a restaurant located at 115 Elfreth’s Alley from 1933 - 1942, offers us another way to look at the service industry in Philadelphia. Remember this from Season 1?

“In 1933, Dolly opened a cafe—called The Hearthstone—in the house at 115 Elfreth’s Alley, commuting over the shiny new Ben Franklin Bridge. Among the sandwich offerings at The Hearthstone were: Creamed Chicken on Toast, pineapple and cream cheese with chopped nuts, creamed beef on toast, chopped olive and nut, veal loaf, tomato and lettuce, green pepper and bacon, and peanut butter and chopped celery. The creamed chicken and creamed beef cost 15 cents; all of the other sandwiches were 10 cents.”

It’s difficult to know what the day to day experience of Ottey and her employees was, but we can try to extrapolate from what we do know about her.

Ottey’s restaurant opened in the middle of the Great Depression and suffered for it. Her story is one where the crisis is palpable. The neighborhood that the Hearthstone resided in looked much different than the Old City we think of today. Factories and warehouses, including the Wetherill Paint Factory, were the prominent features of the landscape in a time before the reimagining of Old City as a cultural asset. Dolley Ottey opened the Hearthstone with the intention of serving both the local and tourist populations with her home cooked meals. She also offered candlelit dinners serviced by staff dressed in eighteenth century garb with a menu that featured the colonial fare like one would find at the original City Tavern. Although we know these dinners took place, there is an incredibly paltry record of who worked with Ottey. One photograph survives in the Elfreth’s Alley scrapbook, of Ottey and her “helpers” all wearing colonial style dresses. The caption refers to the girls as “helpers,” but tells us little else about the role that they would have served. The silence of the archive and marginalization of those in the service industry continued with the Hearthstone and into the 20th century.

Ottey and her “helpers” served home cooked lunches from 11-3 daily, and on Thursdays they served dinner as well. The Hearthstone was also available for reservations for dinners or parties outside of their Thursday schedule. Ottey stressed not only her spatial connection to Colonial Philadelphia, but also the authenticity of that experience through “real home cooked foods, in a quiet friendly atmosphere.” Her emphasis on the aesthetics of the colonial experience represents a trend in historical interpretation that was occurring across the nation.

Ottey was an important figure in the preservation and celebration of Elfreth’s Alley colonial past. The Elfreth’s Alley Association was formed in 1934 inside of the Hearthstone by Ottey and her neighbor, Mrs. Greer. Ottey served multiple roles on the Alley, not only as a business owner but as a community leader. Her restaurant was part of a larger push towards historical reenactment in Old City. The Hearthstone not only served dinner in costume every Thursday, but also became a central meeting place during events like the pageant for the Windows of Old Philadelphia. Photos survive of women lining up outside of the Hearthstone to attend a June luncheon hosted by Ottey and her “helpers,” proving again the centrality of the restaurant to the historical celebrations during the 1930s.

Dolley Ottey was on the cutting edge of the commodification of history in Old City. Despite the long lines for luncheons, pageants and other holidays calling for historical authenticity, Ottey struggled. Minutes recorded from the Philadelphia Society for the Preservation of Landmarks show that in 1936 Ottey struggled to pay her gas bill and asked for assistance. The reliance of her business on holidays such as Elfreth’s Alley’s Fete Day shows a dependence on the tourism industry, which during the Great Depression struggled along with the rest of the country. In 1935 when Ottey was renovating her tea room, minutes from the Philadelphia Society for the Preservation of Landmarks indicated that they hoped the expansion would help her make money, making it clear that even in the early days of the restaurant, money was an issue. By 1941, Ottey was having trouble making ends meet. In November 1942, she closed The Hearthstone for good and refashioned 115 into the headquarters of the Elfreth’s Alley Association. Running a restaurant that relied on tourism proved to be a volatile venture at best, and Ottey’s business did not survive those slow periods.

We can only imagine the difficulties faced by Ottey’s staff as they attempted to navigate their employment in an ever changing industry. Then, as today, restaurant work was often temporary and vulnerable.

As Gwen Franklin, who we’ll hear from later, puts it:

Gwen Franklin: Most people do not enter a service industry for life, like it’s just kind of a way to make money in the moment.

Working for tips makes for an unstable financial situation, and servers likely had to engage in other occupations to make a living. On top of their unstable position working in the service industry during the Great Depression, we wonder about the “helpers” experience in historical reenactment. We know that Ottey offered the traditional dinners served by women in colonial garb every Thursday, and presumably for reserved parties. We imagine these women were also asked to perform emotional labor as they played historical roles and offered smiling service..

Dr. Pilgrim noted that following these “helpers” is made especially difficult by these women’s place in society and in the written record:

Pilgrim: I think the other thing too, you're also dealing with women who are again, people, and this may not be their particular transient, but they're transient as subjects in the archive. Right, that that if they get married, they disappear because nobody is tracing women unless they are householders. Right, like unless they are single, property owning people, right. It's also a job that, as you've already discovered, right, people are always are moving in and out of it all the time.

In 1947, another restaurant opened on the Alley at #135. Called the Coach House Restaurant, it followed the model of the Hearthstone in that it coupled lunchtime, lighter fare, and evening dining with historical ambience. This restaurant also relied heavily on the Elfreth’s Alley Association’s Fete Day, and it’s proprietor, John Duross, was heavily involved in the Association’s activities, even serving as President of the Association for a period. Duross operated the Coach House with a skeleton crew, doing the cooking himself, once an army buddy had shown him the ropes, and employing one waitress. By the mid 1950s, one waitress had been there for seven years and Duross left the restaurant in her hands while he took a two-month vacation. While this small scale allowed for some continuity, Duross’ laissez-faire attitude about making a profit--he admitted to a reporter that he had no idea if he was making or losing money--ultimately spelled the end of the Coach House in 1957. It had lasted for about the same lifespan as the Hearthstone.

Perhaps the Hearthstone and the Coach House Restaurant were too far ahead of their time. By the early 1960s, Elfreth’s Alley was a National Historical Landmark, and excitement for the American Bicentennial was in full swing. As the National Park Service reshaped the land around Independence Hall into a park, it also built replicas of select buildings. Among those structures was City Tavern, which had been demolished in 1854 after being damaged by fire. The rebuilt Tavern opened for business just in time for the Bicentennial, offering visitors to Philadelphia’s historic sites a menu of 18th century foods and beverages. In 1994, chef Walter Staib (Sh-IGH-b), took over the contract with the Park Service from the previous concessionaire and reinvigorated the site, earning plaudits for the food as well as for his television show, A Taste of History, which debuted in 2009. In many ways, Staib and his team at City Tavern continued the vision of Ottey and Duross, its greater success due to a robust tourist economy built by city government funding as well as the work of preservationists at sites such as Elfreth’s Alley.

Conclusion

Franklin: i did lose my job when covid happened so they had closed down completely, they reopened recently at a few places, I think they’re starting to do indoor now. but I opted not to go back just because the way philadelphia’s been handling the pandemic and the food service industry is subpar in my opinion.

That was Gwen Franklin, who we heard from briefly earlier in the episode. Along with Paige Bartello, Franklin not only conducted the initial research for this episode of the Alley Cast, and both of them have intimate experience working in the food service industry here in Philadelphia. They are two of the countless workers and families experiencing financial distress due to restaurant closures. They reflected on their experience researching fellow workers hundreds of years in the past. Bartello said it brought up a lot of emotions--the difficulties in finding evidence of food service workers’ lives echoed her frustrations working in restaurants where she didn’t feel valued.

Franklin: But other than that, like you are just working day to day and the covid pandemic emphasize that for me and its not an industry that you can receive security in and that is what also what we saw in the past too that people weren’t staying in the service industry for very long which is part of the reason why they were really hard to like archivally trace down because they would work there for a year or two and then move on and they would have a longer life as a millworker, they would move to jersey and like these kind of more industrial things that had better records because of tighter regulations. And i think that’s still the reality. I think that’s one of the things that will never change.

From the service industry’s inception in Philadelphia we can trace common threads to our current moment. Food service requires emotional labor, resilience, and uncertainty. With the rise of Covid-19 this past year businesses have experienced familiar hardships tenfold. People stopped going out to eat in the numbers they did pre-pandemic but rent is still due for business owners. Restaurants in Old City rely heavily on tourism to make their money, and while Dollie Ottey experienced hardship going into the slow season, in 2020 the slow season consisted of nearly the entire year. Just as the original City Tavern closed its doors, the modern day iteration was forced to close due to lack of business during the pandemic. As restaurants reopened, workers faced the prospect of exposing themselves to a deadly disease at work, and uncertain schedules as managers struggled to scale back up toward something like normal while being restricted in how many diners could eat indoors.

The restaurant industry has always been rife with uncertainty. Through ups and downs the food service industry has remained a staple of Philadelphia’s economy and a major source of jobs for its citizens. From owners to servers, those affected by the tides of the food industry remain an essential component of our society today.

Centering workers in the history of food service brought up reflections from the historians who worked on this episode and who have experience in the service industry. Hoping that this episode and research can be a starting point for further research into service workers, Franklin and Bartello reflected on the ways restaurant patrons (and listeners of this podcast!) can be empathetic participants in this history.

Franklin: tip your servers. Like if you’re not paying them, no one is. And like unfortunately that’s kind of been the reality in the service industry for its entire existence. If you’re not going to pay the person who is serving you food like neither is their employer. The industry has always been exploitative and volatile. And the only way to really fundamentally change that is to be a decent individual and advocate for a higher minimum wage.

In our interview with Paige Bartello, she also emphasized the diner’s role. In her words, when you are dining out, you “hold someone’s livelihood in the balance like that, when you have that kind of power,” and she encourages listeners to tip generously.

This episode is dedicated in honor of those who worked in City Tavern in 1773 through 2020. Please support local restaurants and, most importantly, restaurant workers. We hope that the next time you eat out, you tip your server well.

History is a group effort! This episode was written by Gwen Franklin, Paige Bartello, Margaret Sanford, and Ted Maust. Thanks to Dr. Danya Pilgrim for chatting with us—her article “Masters of a Craft: Philadelphia's Black Public Waiters, 1820–50” informed much of the section of this episode about Black caterers in Philadelphia. Thanks to Gwen Franklin and Paige Bartello for chatting with Margaret Sanford for this episode--unfortunately, due to a technical issue we were only able to include Franklin’s audio.

Thanks to Keshler Thibert for performing selections from Rober Roberts’ HOUSE SERVANT'S DIRECTORY.

In addition to the scholars cited by name, this episode drew on the work of Mary Rizzo, Peter Thompson, Rebecca Yamin and R. Scott Stephenson. This episode also relied heavily on the Elfreth’s Alley Scrapbook, which contains clippings and ephemera about both the Hearthstone and the Coach House restaurants.

A transcript of this episode with sources is available on the episode page at ElfrethsAlley.org/podcast and the link in the show notes.

The music in this episode is the songs “Open Flames” and “An Oddly Formal Dance,” both by Blue Dot Sessions and both used under Creative Commons license.

This podcast is recorded on the unceded indigenous territory of the Lenni-Lenape people, who were and continue to be active stewards of the land. We recognize that words are not enough and we aim to actively uphold indigenous visibility and sovereignty for individuals and communities who live here now, and for those who were forcibly removed from their Homelands. By offering this Land Acknowledgment, we affirm Indigenous sovereignty and will work to hold the Elfreth’s Alley Museum accountable to the needs of American Indian and Indigenous peoples.

Thank you for listening to this episode of Season 2 of The Alley Cast! Remember that one of the best ways you can support our work is by telling other people about this show and rating us on podcast apps such as Apple Podcasts.

You can sustain the work of the Elfreth’s Alley Museum by making a donation at elfrethsalley.org/donate or by joining our Patreon at patreon.com/elfrethsalley.

See you next week for the final installment of this run of episodes when we talk to Dr. Billy Smith about laborers in Philadelphia.

Thank you and take care!